Dancer from Khiva, The Read online

Page 6

“Yes, I understand.”

They ran away, and even though I felt uneasy, I did what they’d said: I took my panties off, lay down on the table, and opened my legs wide. I lay there on the table with no panties on waiting for that lecturer. And I was dreadfully afraid that I wasn’t a virgin and now everyone would know about it. My heart started beating so hard I thought it would leap out of my chest.

I lay there and several minutes went past. There was nothing, silence. So I just went on lying there.

Then suddenly the door opened, and there was a man wearing a tie, with some kind of file under his arm. I lifted my head up a bit and looked at him from where I was lying. My heart started beating even faster. He just stood there, and his eyes opened as wide as headlamps. The poor man stood there and didn’t move, not a muscle. He looked at me, and he seemed to be surprised, and I looked at him, and I was surprised too, and I wondered why he didn’t come over to me and check if I was a virgin or not. It was strange!

But he stood there just like a statue.

Eventually the director came up behind him and screamed:

“This is outrageous! All right, get up!”

Of course, I was startled and confused. I got up quickly, put on my panties, and looked at the man. The poor creature was still standing there with his mouth open. And the director said:

“Go on, call all the teachers and nannies, quickly, I want them all to come here!” Of course, I called everyone to join the group. They all came and sat on the chairs. And the man in the tie went up to the table where I was lying earlier, opened his file, took some papers out of it, and started talking about something, I don’t remember what it was now. And he kept looking at me.

I thought: Why didn’t he come over to me? It’s strange, why is he reading some papers or other? Why didn’t he check me?

Afterward they told me a lecturer reads lectures and doesn’t check girls. And like a fool I’d been lying there on the table without any panties on and with my legs open wide.

In the kindergarten I worked until three o’clock in the afternoon. And I was still living with Svoboda Vasilievna. She had a friend, or partner—Uncle Zhora, a ballet-master. His apartment was in a different district, but he often visited Svoboda Vasilievna and stayed for the night, or even lived there for weeks at a time. Sometimes, even quite often, he would arrive drunk and start yelling and kick me out into the street.

And then the fall came. It was already November. One day Uncle Zhora arrived drunk and put on his usual performance and started a fight with Svoboda Vasilievna. They quarreled very badly. And then he attacked me and again kicked me out. I took offense and ran outside in nothing but my thin housecoat and my slippers. I walked along, crying. It was a Saturday. The kindergarten was closed for two days.

I walked round the railroad stations, wandered round the streets, and I didn’t have a kopeck in my pocket. It was already evening and very dark. Then I sat in the waiting hall at a railroad station, but not for long, because the militiamen were checking people’s documents and tickets. I wandered around in the cold until the morning, but I didn’t go back to Svoboda Vasilievna’s apartment. Then I suddenly remembered Anna Petrovna’s address—she was a teacher at the kindergarten.

Early on Sunday morning, on the second day, I went to her. She was very upset and said:

“I’d be glad to let you stay with me, but besides me, my sister and her fiancé also live here, and it’s very crowded.” It was true—she lived in a communal apartment.

And I had to go back out on the street again.

It was very cold in my thin housecoat and slippers. It was the second night I hadn’t slept. Before morning came I must have walked round all of Leningrad. I was hungry and cold. Early on Monday morning I came to the kindergarten and ran round and round it so I wouldn’t freeze. At about six o’clock the cooks came and opened the door. I dashed toward them straightaway. They saw me and asked:

“Bibish, why are you here so early, why have you turned blue, why are you so lightly dressed?”

But I didn’t have the strength to answer them. They opened the door, I went in and fell over in the lobby. When I came round I saw I was in the closet, that is, in the little room where the mattresses were kept. They must have dragged me in there so I could catch up on my sleep. I slept for a whole day and night. No one woke me up. When I came round, the teachers advised me:

“Go to the director. Say she must give you a place to live. You can’t go on like this, you’ll kill yourself.”

I went to the director:

“Zinaida Alexandrovna, I’d like to ask you if I can have a room in a communal apartment to go with my job, please help me.”

But she shouted angrily:

“I know you people! First you work and then, as soon as you get a place to live, you hand in your notice straightaway, and who’s going to work for me? No one! You can’t have a room. I heard you spent two days wandering round the streets, but what can I do about it?” She paused and then said: “All right, I’m not made of iron, I’ll allow you to live here, in the kindergarten, stay after work and live here. In the evenings the watchman, Borya, comes, and the two of you can guard the kindergarten. Now go and work.”

I was really delighted that now I wouldn’t have to hang about outside at night and wander the streets until morning came.

From that day on I stayed in the kindergarten after work. I lived on the second floor in my group’s classroom. The watchman Uncle Borya said:

“It’s a good thing the director said you can stay here. I’ll be able to go home now. Only don’t you tell the director.”

And so he always went away, and I was left alone. And he also warned me:

“Don’t keep the light on, or the drunks might throw a bottle through the window.”

And so I used to stay in there without any light until the morning. I always ate cold food, what was left over from the children’s meals, or from the ones who hadn’t come to the kindergarten. On Saturday and Sunday I was almost always hungry, because what I saved wasn’t enough for two days.

At that kindergarten I was reminded of my own preschool in the kishlak. A government commission checked it every so often. When the teachers heard the commission was coming to check them, they went out “hunting” with their director. They looked for children everywhere. When they found some, they tried to persuade our parents to let us attend the kindergarten temporarily. As soon as the commission left, we were sent home straightaway. At least we got a chance to eat something nice while the check was going on, but afterward they stopped feeding us properly. Sometimes I had to go to the kindergarten even when there wasn’t a commission. Then what the caretakers did was first eat the main dish in the office with their own children and give us just the soup with nothing else, and so we didn’t want to go to the kindergarten. We tried to go only when they had a commission, so we could have something nice to eat. But they begged only the parents to bring their children so that the kindergarten wouldn’t be closed. And they always got away with it.

And so I lived like that for eight months, all alone in the kindergarten in the evenings, without anyone else.

Sometimes I went into the city for a little while, to the long-distance public telephones, to call home. To reassure them, I said I’d got into the university and was already attending classes.

It was difficult. The low pay was never enough. The money ran out very quickly. In the streetcar I always tried to stand next to the ticket dispenser, and when people handed on the money for a ticket to me, I tore one off for myself as well, making sure no one saw me. It was shameful, but what else could I do?

And I remember, when I was living in the kindergarten, one of the teachers used to come every Saturday and Sunday and call up to my window: “Are you still alive?” She used to bring me hot tea in a thermos. I was so glad when she came! At least there was someone to say a few words to.

Winter came. It was cold. All the ground was covered with snow. The bla

ck ice made it impossible to walk. Once I went into the city to buy an envelope. I walked along the narrow paths that had been swept clean in order not to fall.

Suddenly I heard a voice, an old granny calling:

“Daughter, help me, give me your hand!”

I didn’t know that in Russian the word for meant “pen” could mean “hand” too. I answered:

“I haven’t got a pen,” and continued walking, thinking how I should have brought a pencil with me. Then I looked round and saw the old granny was sitting on the snow, trying to get up.

I went back to her and helped her up, and she said:

“Good, thank you, at last you understood!”

I often used my “knowledge” of Russian in the wrong way. This is what happened another time:

I already knew that Leningraders are cultured people, and they talk to each other very politely. And I wanted be like them. One day I got into a bus to go somewhere. There were a lot of people in the bus. And then one of the passengers, a woman, sneezed. I turned round and said:

“Bless you!”

And she replied rudely:

“Mind your own business!”

After that answer I never tried to be polite in public transport again.

So that was how I lived in the city of Leningrad.

One day I decided to phone Giya, the student who lived on Warsaw Street, the one I went looking for during my first days in Leningrad, and his mother wouldn’t let me into the apartment. His mother answered:

“Yes, yes, hello.”

“Is Giya there?”

“Who’s asking for him?”

“I’m Bibish.”

“What Bibish?”

“The one from the East, from Khiva.”

“Wait, wait, the one with the braids? Right?”

“Yes, that’s me.”

“Where are you, for God’s sake, don’t hang up!”

“All right. I’m calling from work, from a kindergarten.”

“Why didn’t you call sooner, how could you do that? I gave you the number!”

“I didn’t want to bother you, especially with Giya not there.”

“Bibish, when he came back from the East, of course I told him you’d arrived, and he asked: ‘Where is she then?’ I said: ‘I don’t know, she was going to join the history faculty, or maybe some other.’ And he got angry and said: ‘Oh, mom, what have you gone and done! Bibish’s mother had nine children, but she spent days and days helping us in Khiva! And she spent her own money, she took us to a party, she saw us off to the railroad station, she gave us souvenirs. You can barely manage just to bring me up, and now with all your principles, you’ve sent her back out onto the street! Mom, how could you? She doesn’t know the city, if she came here, it’s because I gave her the address. Mom, think what you’ve done! Now where can I look for her?’ Then I went to the university and looked for you everywhere in the lists of applicants who got in or didn’t get in, but it was all futile. He reproached me every day because of you. But I was still hoping you would phone. Can you hear me, Bibish, can you come to visit us? What a nice surprise it would be for Giya!”

“I can hear you, thank you, I’ll definitely come, only I can’t come today.”

“Then when will you come?”

“Let’s say the day after tomorrow, five o’clock.”

“All right, we’ll be expecting you. Only before you come, call first, all right?”

“All right, I’ll definitely come.”

That was how our long conversation finished. Two days later I called and Giya answered. He was delighted and said he would meet me outside in the street. So I went visiting.

He really was waiting for me with flowers, and when we met he kissed me. His mother, father, and grandmother were waiting for me at home. They fed me Georgian food. The conversation wasn’t working out though, because of me. Giya’s mother kept saying how Giya had tormented her and how she’d looked everywhere for me. And I sat there without saying anything, listening, and just nodding my head.

Then Giya said:

“This won’t get us anywhere, just a minute, I’ll be back.”

He went out. After half an hour he came back with a girl with a dark complexion and said:

“There, I’ve brought you an interpreter. Now I hope you’ll understand each other. This is Rano, a Leningrad University student from Tajikistan.”

This girl had very long, beautiful braids. Well, of course, with an interpreter it was easier for all of us. Poor Rano translated. She did the best she could, because she was Tajiki, and I’m Uzbeki, and the languages are different. The Tajik language belongs to the Persian group, and the Uzbek language belongs to the Turkish group. Luckily Rano could speak a little Uzbek. A few years later she and Giya got married.

After supper they wouldn’t let me go, and I stayed in their home for the night. In the morning Giya’s mother invited me to go for a walk round the city.

“I’m so ashamed, you were probably left out on the street because of me, Bibish,” she said and started to cry.

I think she worked as a research assistant in some institute, I don’t remember now.

I told her about myself, and then she said:

“But if you’re living in that kindergarten without any light or any food, that’s very bad. I’ll ask Giya, maybe he’ll find a place for you in the hostel with the students in his year.”

We walked round the city, then went home and waited for Giya. He came back after his classes, his mother explained everything to him, and Giya and I went to the hostel. I saw my old friends Zarina and Svetlana there. We remembered how we met and had a good laugh. The girls agreed to do what Giya asked and let me stay in their room in the hostel. They arranged things with the doorkeeper, and she always let me through. So it was all right.

I worked in the kindergarten until three o’clock, and straight-away after work I ran to the hostel. I got to know more students: Berid from Germany, Tkho and Lok from Vietnam, Arkasha and Bator from Mongolia, Ira from Buryatia. I remember I used to bring the girls food that was left over at the kindergarten after the children’s meals: rissoles, apples, omelettes . . . You know, students are always hungry.

And everything was fine, until they changed the doorkeeper in the hostel. Now the new doorkeeper asked everyone for their passes. One fine day she refused to let me in and said: “Show me your student card.” But I didn’t have one, so I was left out on the street again.

To be honest, I didn’t want to bother anyone anymore, so I simply walked away from the hostel and wandered the streets again until the morning, like a tramp. I was frozen and exhausted and I thought: Why does everything turn out like this for me? Why is my life so cursed, and what’s the point in living if it’s like this?

And so I walked on and on round the streets, then I stopped and lay down on the concrete so that a car would run over me. I lay there and waited. I couldn’t care less about anything, I just wanted to die as soon as possible, that was all.

Suddenly a car stopped. A man jumped out of it, ran up to me, and shouted:

“You shouldn’t drink so much! These young people nowadays!”

I lay there and cried and I didn’t answer.

He half lifted me up from the road.

“But you’re sober!”

I didn’t say anything.

“All right, get up!”

“I won’t, I want to die.”

“Enough of that! You’ve plenty of time to die. It’s all ahead of you, get up. Where shall I take you?” He helped me to stand up.

“To the bypass canal embankment, that’s where I want to go.”

“Another fine idea! Now you’re going to drown yourself?”

“No, I already tried to drown myself. It didn’t work. Someone I know lives near the bypass canal.”

“That’s a different matter. Let’s go then.”

And so there I was, still alive.

I went to see Anna Petrovna. She introduced me to a fr

iend of hers, and I lived with her for a while.

But how long could I keep on wandering from one stranger to another? One day I came to work and told Anna Petrovna I was really desperate and asked what I should do.

She sighed and said:

“Listen, go and see the Duma deputy for our district. Kirill Lavrov, the People’s Artist of the USSR. Perhaps he’ll help you.”

So I went for a consultation with the deputy Kirill Lavrov, but when I saw him in the corridor, so handsome in his suit and tie, I felt embarrassed and went back to the kindergarten.

I suffered like that for about ten months. Then I had to leave my job and go back to my native parts, to my kishlak in Uzbekistan. What else could I do now, with no apartment or work or place to study? Nothing had worked out for me. I had no money, I didn’t know Russian, and I had no one to support me. I didn’t want to be a burden to my friends, they all had their own lives. It made me feel so sick to go back! But what else was there left for me to do? I had to accept it. And that was all.

I remember I didn’t even have any money to get back. Giya and the other students and Genriko Sergeevna collected the money for the ticket. I said good-bye to them and got into the train. I traveled for three and a half days without eating, because I had no money left.

I barely made it home.

The kishlak again, and all the same people, the same glances, the same gossip. Hard times were beginning at home just then. There was no money, barely enough even for bread.

One day I found out that one of our neighbors had gone to the city of Samarqand and danced there at weddings and brought back a lot of money. Straightaway I thought: Why shouldn’t I go and earn money at weddings? In the East they give huge money to dancers. Since I couldn’t dance where they knew me, I went away to a different region. After all, if anyone found out that I danced at weddings, no one would marry me.

I was eighteen. Stupid and naive. It’s very hard for a young girl without experience to go and dance at a wedding. I found out in secret the best way to get to Samarqand, how to find the right address, and where to stay. Then I went to earn some money.

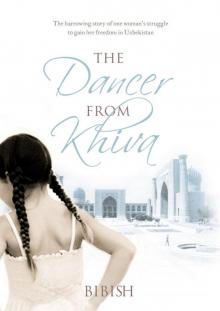

Dancer from Khiva, The

Dancer from Khiva, The