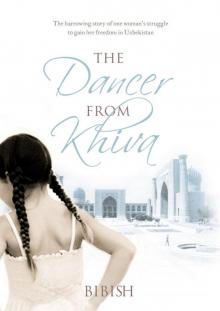

Dancer from Khiva, The Read online

THE DANCER

FROM KHIVA

Originally published in 2004 as Tantzovschitza iz Khivy, ili Istoria prostodushnoy by to Azbooka-Klassika Publishing House.

First published in English in the United States of America and Canada in 2008 by Black Cat, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2009 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright © Bibish, 2004, 2005

The moral right of Bibish to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

Translation copyright © Andrew Bromfield, 2007

The moral right of Andrew Bromfield to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 84354 623 8

eISBN: 978 1 84887 374 2

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

This book is dedicated to my American friend, Linda Harris

I will tell you my story to unburden my heart a little. I think you will surely read the story of my cursed misery to the end. That is my hope.

I come from the East. Yes, I was born in Uzbekistan, not far from Khiva, in a very religious area with its own harsh, merciless laws and customs, its own strange and vicious ways of looking at life.

There is a legend about how Khiva got its name. An old man wandered through the desert for a long time in search of water, he was very thirsty. And finally he found a well. After quenching his thirst, he exclaimed “Khey, vakh!” in his pleasure. After that a town sprang up round the well, and they called it Khivak, and later they started saying simply Khiva. Much earlier, almost two thousand years before, the ancient state of Khorezm was here.

At one time, before the October Revolution, we had a khanate here, and in Russia they had tsars and emperors. Of course, you know about that. Well, the khan of Khiva had many slaves from many different countries. They all toiled hard for him. One of these slaves was my mother’s father, who was brought from Iran as a child.

There is one other thing I would like to say about Khiva: Our former leader, Lenin, had only one single medal, which was given to him by my fellow townsmen of Khiva. Lenin did not have any other medals or orders at all.

Yes, I was born in a small kishlak, or village, from where we could glimpse the minarets of Khiva. The dreadful thing, as I have said, is that the people there were terribly religious. They observed the laws very strictly, and there was slander and rumor on every side.

My mother’s father was known as Kurban-kul, which means “the slave Kurban.” He served the khan right up until the revolution. He looked after the camels and fed them. He was a camelherd. When the October Revolution happened in 1917, the Red Army liberated the slaves. But my grandfather could not go back to his homeland in Iran, so he stayed in the village and married a Uzbek woman, my grandmother. They had a little girl, my mother, and another seven brothers and sisters. My mother grew up, and when she was eighteen, she married my father.

You would probably like to know why I am called Bibish. My full name is Hadjarbibi. Hadjar is from the word hadj, a pilgrimage. Every devout Muslim, if he is able, must make at least one pilgrimage to Mecca or Medina.

My father’s grandfather was called Iskhak Okhun, he studied in a madrassa and was the imam of the kishlak. And Okhun’s father was the secretary of the khan of Khiva. Okhun walked all the way to Mecca to make his hadj. When he came back, he was considered the most pious man in the village. And he told my father, who was only a little boy then:

“My grandson, when you marry and you have a girl-child, name her in honor of my pilgrimage, and let her be as holy as the hadj.”

And so I was born Hadjar. And bibi means a woman. Together they made the name Hadjarbibi. But when I was a child I was called Hadjar most of the time. Then when my future mother-in-law saw me for the first time, she said: “What a long name—Hadjarbibi. It will take a hundred years to say that. Let’s call you simply Bibish!” And so I became Bibish to everyone.

My mother had nine children. In a single year, 1978, two of my brothers and my sister died of different illnesses. And so there were six of us left in the family. One of the boys who died was twelve years old, the girl was two years old, and my youngest brother was only seven days old. I feel so sorry for them.

We lived a very poor life. My father was a teacher in the local village school. My mother didn’t have a job anywhere. She only picked cotton in the collective farm during the season.

My mother was very beautiful, her braids were very long, right down to her heels, thick and black. I remember her face, with smooth skin that glowed. All her neighbors and friends used to ask what her secret was. And I remember our father used to take us into the town on his bicycle (all our father had was a bicycle that was put together out of parts from other bicycles). In the bazaar my father used to buy us apples and melons that were almost rotten. Now I understand why he did that—there was never enough money to feed us.

In the place where we lived, if you pushed a stick into the ground, it would blossom and give fruit. But the problem was that, apart from the school where he taught Russian and Arabic, the only thing my father did was read books. Apart from books, nothing interested him. And it’s still the same now. Now he reads not just with glasses, but with a magnifying glass too. And so nothing ever grew in our garden but rushes and grass.

Now I will tell you about the most painful thing that happened in my life. Almost thirty years have passed since that day, and all those years I have kept the memory to myself. I have never shared it with anyone: I was afraid to tell anyone about it.

One summer (I was eight years old then) I asked my mother if I could go to see my grandmother and spend a few days with her. My mother said I could. So I set off. Grandmother lived more than three kilometers away from us. We always walked when we went to see her. I would go on my own, or with one of my brothers, sometimes we walked there with our parents.

So I went out on to the road. And I walked. It was summer, and hot. If you’ve ever been to our parts, then you know what the heat is like there. Sometimes the temperature reaches forty or forty-five degrees.

Like my mother, I had long, thick braids right down to my heels. And I was plump too. Everyone in the kishlak envied me for having such long braids. My mother always looked after my hair: she used to wash it with the whey from buttermilk and comb it.

And so I walked along. I hardly met anyone at all on the road. One or two people went by with donkeys, that was all. Then I looked back and saw a huge car, probably a jeep, in the distance, coming toward me. The car stopped. A man jumped out, and just like that, he grabbed me and threw me into the car. Two more men were sitting in the car. I began to cry. Then one of then shouted:

“Shut up, or you’ll get it!”

I was

frightened and I cried quietly, without making any sound. My heart was pounding so hard! The car was moving very fast. One of the men kept hugging me all the time, squeezing me against him, and saying:

“Would you believe it, she still smells of milk. We’re lucky, she’s fresh, a gift from heaven!”

We drove for a long time and went far into the desert. All I could see all around was desert. It was already afternoon. The driver stopped the car a very long way from the highway. There were thin, prickly bushes growing where the car stopped.

They left me beside the car and walked off to one side. They argued with each other about something for a long time. They shouted and swore. I didn’t understand anything they were saying. Then they sat down and smoked something. And then they began laughing like madmen.

I was so frightened I didn’t know what to do. So I decided to run wherever my feet took me. I didn’t know where I was running to, my head was completely empty. They dashed after me, caught me, and started beating me. They started strangling me with my braids and shouting:

“Where are you running? You’re shivering! Are you cold, then? Come to me! You can shout here, no one will hear you!”

They beat me badly, then one of them held my hands in his hand and wound my hair onto his free hand and pulled me toward him, so I couldn’t break free. Another one began tearing off my dress and the trousers we wear in our parts, which are called bakakly-ishtan. I started crying loudly—it hurt a lot when he pulled me toward him with my hair wound round his hand. The pain was terrible.

One said:

“Look, she hasn’t even got any tits!”

Another said:

“Come on, get on with it, we’re wasting time.”

“What if she doesn’t survive?”

“You let me do it, then. And don’t worry. If she doesn’t survive, the desert’s a big place. We’ll set fire to her and bury her. Come on, if you don’t want to do it, move aside!”

Then one of them fell on me as hard as he could, and I passed out. What they did to me is known only to God. They tormented me so viciously, there are no words to describe it. They raped me mercilessly.

Because I didn’t move and didn’t react, they probably thought I was already dead. They must have been frightened, so they buried me in the sand. Then they drove away.

I don’t know why they didn’t burn me as they were planning to do. Perhaps they had run out of matches. Perhaps they simply took fright and decided that if they buried me it would be enough. It’s hard to say what they were thinking after my “death.” They started hurrying and didn’t bury me deep in the sand. Praise be to God! But how much time passed while I lay buried in the sand, I don’t remember.

The sand was very hot. Probably that’s why I came round. At first I couldn’t move. The sand made my eyes itch, my mouth was full of sand. I barely managed to drag myself out. I was very thirsty. All I wanted was to drink. I had terrible pains all over my body from the abuse and the beatings.

I saw my torn panties still lying in the sand. Then I walked in the scorching sun. The sand flies and gadflies bit me all over. And at night it was very frightening. The snakes and lizards come creeping out at night. There’s nothing more terrible in deserts at night than poisonous snakes and lizards! And I had enough sores of my own without them: swellings from the insect bites covered my whole body.

I kept coming round and passing out again. I was so terrified I hardly opened my eyes. I never stopped crying and calling for help, but no one heard me.

All day long I was tortured by the heat and longed for water. But where could I get water? When night came, I was tired, I lay down, looked at the sky, counted the stars, and fell asleep. And even in my sleep the only thing I thought about was water. Although I felt very hungry as well.

In the morning I tried to stand up, but I couldn’t, because I wasn’t strong enough. When I got up, I fell down, I couldn’t keep my balance. So I just lay there. Where could I move to anyway? There was no shade anywhere around. There was nowhere to take shelter. Naked desert all around . . .

In the afternoon a flock of sheep passed close by the place where I was lying. Suddenly I felt someone opening my eyes with his fingers. I looked and saw an old shepherd standing over me and looking to see if I was dead or alive. He tried to get me up, but I kept falling down. I felt very ashamed that I didn’t have any panties. I pulled my dress tight round my legs and cried miserably. Finally he got me up, then gave me his stick. He supported me with one hand and began dragging me like that. And we walked for a long time, because I kept falling down. I didn’t have the strength to walk.

He took me to his rough shelter made of branches and gave me water from a jug—by then I thought I was going to die any moment without water. It was warm, but it was still water.

Then he washed the sand off my head with the water. I was a terrifying sight. The sores from the insect bites on my arms and legs had festered and they were very painful. At night I kept getting up all the time and drinking warm water. Then I sank back into delirious sleep. I probably had a high fever, because my entire body was shuddering with cramps.

I didn’t know how many days I spent with the shepherd, and I still don’t know now. After all, almost thirty years have gone by. And how can you count time in the desert? I remember I was very hungry. And what food can a shepherd have in the middle of the desert? Flatbread cakes are the only food I remember. But after so much suffering and hunger, even coarse bread tasted good to me.

Every day I squeezed the pus out of my sores. To this day I still have big scars on my arms. They remind me of this story.

I stayed with the old man in his rough shepherd’s shelter. I remember he had a radio and sometimes it used to play music. I thought there was nothing else in the world except this desert, the shepherd, and me.

Before I’d even recovered from one terrible disaster, there was another. Soon the shepherd began pestering me.

“Don’t be afraid, I won’t touch you, you just stroke it with your hands.”

You understand what he was asking me to do.

I began to cry, and he shouted at me:

“You’ve been with men, what difference does it make to you? You’re not a virgin anymore! If I hadn’t happened to pass by with my herd, you’d have died, and the wild beasts would have eaten you ages ago! I’m not asking you for much, just stroke it, that’s all, and I’ll be satisfied. And stop crying, I’m sick of it. Always crying, when there’s nothing to cry about! Those things that happened are all over now. Be grateful that I saved you!”

One day the shepherd took his flock a long way away. I’d already decided to run away before that, and so I did. I set out to look for a road to the highway. It was hard for me to find that road in the middle of the desert. If only you knew how I suffered because I didn’t have any panties! Just imagine how bad I felt without them and my trousers. And my dress was very dirty and torn. I had to go just as I was.

I finally found the highway, but I was afraid. I felt ashamed to go out on it. And so in the afternoon I lay down beside a prickly bush, and when evening came, I set off along the highway, walking through the sand. I was walking barefoot, and the sand was hot, it was blistering hot under my feet. I walked a little bit, then rested a little bit. That was how I walked. It was a good thing I’d taken some water with me in a bottle. I drank the warm water one mouthful at a time, very sparingly. But even so it was soon finished.

On my way I saw all kinds of snakes and lizards. I couldn’t sleep because of them. And at night it was so quiet, and the stars were so clear and beautiful! There was just a light breeze blowing. Of course, I felt thirsty and hungry again. And my feet were hurt badly by the prickles and the heat—my heels were cracked all over.

Finally one night (the snakes hadn’t touched me!) I came to a kishlak. I saw a well beside the first house and lowered the bucket into it, but it got so full I couldn’t lift it back up. It was too heavy for me. So I dropped it into the well. And I didn’t

get a drink of water after all. But I was so thirsty! I walked round the kishlak for a little while and found an aryk, a small irrigation ditch, with cloudy, muddy water. So I drank some water from the aryk. What else could I do? At least I quenched my thirst. But after that my stomach started gurgling because there was nothing in it except dirty water.

I slept until morning near someone’s house beside a garden. In the morning I got up and walked round the houses. I knocked at the gates and begged. I asked people to give me something to eat. Some of them gave me a lump of sugar, and some gave me a few bread cakes. Others wouldn’t even let me in. They said:

“Go away, we can’t even feed our own family!” Many of them gave me fruit. There’s plenty of fruit in our parts. And so I ate my fill and was satisfied for the whole day. The people there probably thought I was a Tajaki gypsy, whole families of whom wander around begging. They’re everywhere, in Russia and in Uzbekistan, and now everywhere in the Commonwealth of Independent States too. That’s their tradition—to live by begging.

Then I saw some children playing beside their house. I saw them, and I started to cry. It was already late, but it was summer, so it was still light. I stood on the asphalt and cried, and the children called me Baba-Yaga, like the witch in the fairy tale, because I was very dirty. Then some people came up to me and started asking where I was from, who my parents were, where I lived. And I told them I’d got lost.

I remember someone there even felt sorry for me: “Give her a wash and some clothes and she’d be a normal little girl.”

They decided to send me home. They found a man with a motorbike and asked him to take me. Of course, they questioned me first. But I didn’t know the name of the collective farm where my kishlak was. I knew there were lakes somewhere nearby, but that was all. Then they asked me what people called my father. I said, “Teacher.”

And finally he took me home. I slept all the way in the sidecar of the motorbike, because I was exhausted.

Dancer from Khiva, The

Dancer from Khiva, The