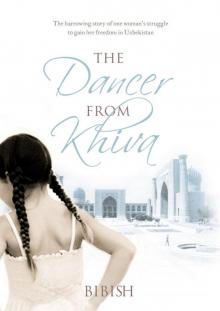

Dancer from Khiva, The Read online

Page 10

During the first period of our life together, I noticed that my mother-in-law slept apart from her husband. I started wondering why. My parents had always slept together, but every evening Ikram’s parents went to different rooms.

I asked Ikram:

“Why does your mother sleep separately from her husband? After all, she’s still young.”

“She’s not well,” Ikram replied briefly.

“What has she got?”

“I don’t want to say. Ask her yourself.”

“It seems awkward somehow.”

“What’s wrong with it? Ask, and you’ll get to know each other better as well.”

One day I finally plucked up my courage and asked my mother-in-law about her life. I made tea for when she came home (we used to drink green tea before a meal in order to stop ourselves feeling tired). We sat at the table in the huge kitchen.

“How is your work going?” I asked. “Is everything all right?”

“Everything’s fine. I am working on a report.”

I was tormented by curiosity. I gave her some tea and said:

“Mom, tell me about yourself.”

She laughed:

“Are you interested?”

“Of course!”

“All right then. But it’s a long story.”

And she started telling me.

My Mother-in-Law’s Story

My mother and father came from Russia, from the Ulyanovsk region. My mother didn’t speak until she was nine. One day my mother’s older sister grabbed a burning stick out of the stove, held it up to her mouth, and said:

“Come on, now, say ‘mama-papa’!”

My mother was frightened and she shouted: “Mama! Papa!” and then hid under the bed. Her sister ran to their parents to tell them the little girl had said something. After that she began talking. But my mother finished only three grades of school.

She grew up and married a young man from her village. When they got married, someone jinxed them: they couldn’t live with each other as husband and wife. Then they went to a healer. The healer advised them to go away from the village. And that’s how my parents came to be in Uzbekistan. My father worked as an irrigator: he used to measure the level of the water in the Amudarya and its tributaries, and sail along the river in a boat. But later the people he worked for sent him to study. And soon my father was transferred to work in Turkmenia.

The first child they had was a boy, Boris. Once they had to travel through the sands on camels. It was very hot. The little boy caught dysentery and died. At the new place in Turkmenia, I was born. Then came my sister and my brother.

When the war started, my father went to the front. My mother was left alone with three children. She got work with the post office, delivering telegrams. She had to work even at night. There were a lot of death notices. My mother used to suffer for everyone who had been killed.

After that she moved to a different job—she used to spray small marshes with chemicals to kill mosquitoes that carried malaria. And she used to deliver quinine—the medicine for malaria—to people who were sick. Sometimes she took me with her. The collective farm people used to live in shelters made of branches. They didn’t even have doors.

It was very difficult for my mother to feed us. She collected the last of her things—pieces of satin, plush, and cotton cloth—then she went round the villages and exchanged it all for a cow. Now we had milk.

When I started school my mother made me a bag in the shape of an envelope out of scraps of material. There weren’t enough textbooks. To get something to write on, we used to go to the wastepaper depot and look for blank pages in the books. Sometimes we used to write on newspapers.

One day my mother got a letter from the front. They wrote that my father had been wounded in the collarbone and he was in the hospital. They hadn’t been able to get the bullet out. My father was sent to the rear, to Chelyabinsk, to join a flying group. He served there until the end of the war and then came home.

Soon after that he was moved to the town of Kerki on the banks of the Amudarya. My mother didn’t work, she looked after the house.

After I graduated from a seven-year Russian school, I went to study in Ashkhabad with several other girls. We traveled in train cars that carried cargo, because we didn’t have any passenger trains back then.

When I finished my studies, I was assigned to the town of Tashauz.

During the times when I was young, there weren’t any televisions or tape recorders. The young people used to go to the town park in the evening. There was a dance floor there, and an open-air movie theater.

So I used to go to the park too, with my friend Nina. She was my very best friend, we’ve been friends for more than fifty years.

It was spring, early March. The cherry and apricot trees were covered in snow-white flowers, the apple and peach trees were just beginning to put out pink blossoms. It was very beautiful.

At first Nina and I were going to go to the open-air movie theater, but then we heard the music from the dance floor, and went running over there. A brass band was playing. We really put our hearts into the dancing: the waltz, and the tango, and the foxtrot.

Then suddenly we saw some young men who lived on the same street as us. They were quarreling with someone. We went over, to prevent a fight, and persuaded them to walk home with us.

There was a young man about average height walking beside me. I hadn’t met him before. He had a dark complexion and curly black hair. We walked along without speaking, then suddenly he said to me:

“Are you from round here? I haven’t seen you before.”

“I’m from the district, I haven’t been here long.”

“What’s your name?”

“Raya.”

“My name’s Kadyr. Are you a student?”

“No, I’ve finished my studies. I work now.”

We talked for a long time. I found out he was in the Soviet Army, he’d come there on vacation, and his leave ended the next day.

He stuck close beside me. And then he said in a very familiar tone:

“I’ve really taken a liking to you. Let’s go to my place!”

I was indignant and I answered: “No!”

I had to stay with my friend for the night so that Kadyr wouldn’t find out where I lived. I said good-bye to Kadyr in front of her house, and we left him. He started banging on the door to be let in. But we didn’t react.

Early in the morning I had to go to work. I opened the door and saw Kadyr lying on the doorstep! He got up straightaway and said:

“Forgive me, please, but I couldn’t go away after I saw your blue eyes and light brown hair. I want to be beside you all the time.”

He walked me to work and left. After that I didn’t see him for a long time.

Time went by and I worked and helped my mother with the housework. One day my younger sister came back from the park and said:

“Listen, Raya, there was a young man asking about you at the dance.”

“Who’s that?” I asked, surprised.

“How should I know?”

“But what does he look like?”

“He’s medium height, with curly hair, very attractive-looking, actually.”

I realized who she was talking about and thought:

So, Kadyr has come back from the army. The next weekend I went to the park with my girlfriends to go dancing. When we got there, we sat down on some benches. The music started to play. Everybody went off in pairs to dance, and I was left sitting there. Suddenly I saw a familiar face among the dancers: it was Kadyr dancing with some girl. And then our eyes met. He left the girl in the middle of the dance floor and came over to me, took hold of my hands, and asked me to dance.

Our love began from that day.

We used to meet often and go swimming with our friends or go out into the country. Kadyr was very jealous. He didn’t like it if any of the young men came near me. Sometimes it ended in a fight. Because of his hot temper we used to have

quarrels too. But I put up with it all and forgave it all because I loved him very much.

And then we decided to get married. But my parents were against it. They wanted me to marry a Russian.

My love flared up more brightly with every day, and I decided to leave home and go to Kadyr. And so I went straight from our latest date to his house.

As well as Kadyr’s mother and father, his half brothers and sisters lived with the family.

Kadyr’s mother was called Nazira. She came from Khiva. Her father was a very rich man, and he had married his daughter into a rich family too. She had children—a son and a daughter. But just at that time Stalin’s campaign against kulaks, the landowners, began. Nazira’s father and her husband were exiled to Siberia, and all their wealth was confiscated. Nazira was left alone with two children. Some time later Nazira’s father came back from exile and came straight to Turkmenia, without calling at his home in Khiva—he was afraid they would take him again.

He was very concerned about the fate of his daughter and grandchildren. Soon after that he married her off again to a craftsman from Tashauz (he made traditional metal-bound trunks). Nazira had a lot of children by her new husband, but only three of them survived. Kadyr’s stepfather regarded him as his own son, and he passed on his trade to him and his half brother.

Although I was a Russian-speaker, I was accepted in the house and respected.

At that time Kadyr graduated from teacher training college and went away to work where he was assigned, in Kunya-Urganch, as a teacher of Russian. But I stayed with his parents, since I was pregnant. He only had to work there for a year, so I decided not to go.

The first child we had was a daughter. Then came Ikram, your future husband. Then our youngest son.

Our financial situation improved. Kadyr began to be appointed to various high positions. Of course, he joined the Party. His character gradually began to change, but I didn’t notice that. Or rather, I didn’t want to notice.

There was nothing that we were short of. People in the districts that he supervised used to send us food and even sheep.

Every year we went to resorts. Although we always went separately. Once I went to a sanatorium in Sochi. I saw that all the women were going to the gynecologist for a checkup, and I decided to go and get myself checked too. And the doctor said to me:

“You have to be examined in the cancer clinic.”

“What for?” I was surprised.

“Nothing to worry about, just for prophylactic purposes,” she reassured me. But afterward it turned out she’d said that only women from Central Asia were so badly neglected.

I came back home and told my husband everything. We were both forty then.

“Let’s go to Ashkhabad tomorrow, they’ll cure you there, and everything will be all right,” he said.

The doctors at the hospital in Ashkhabad wouldn’t let me leave, they said I had to stay.

Kadyr bought me everything I needed: slippers, towels, a dressing gown, a kettle, a mug. He said:

“You get well. I’ll phone you often.”

They started giving me radiation treatment immediately. I didn’t get out of bed for three months. And all the time I was thinking about the children and what would happen to them if I died. Sometimes I cried.

At first Kadyr used to phone, then it was less and less often. He said he was very busy at work.

I found out afterward what happened when Kadyr came back home from Ashkhabad. When he got back, he phoned his relatives and his sisters and told them his wife was in a cancer clinic.

They told him:

“Then that’s the end, your wife won’t come back alive.”

Others said:

“It’s a terrible illness. You’ve been unlucky, Kadyr.”

And his sister said:

“See, if you’d married an Uzbek woman, the whole house would have been made of gold.”

In short, everyone expressed their own opinion. Kadyr didn’t say anything in reply, he just listened. After a while Kadyr’s sisters came to him and began trying to persuade him:

“Kadyr-aga, we’re suffering so much for you! Can we tell you some news?”

“What news is that?”

“We’ll tell you, but you promise you won’t be angry.”

“Of course I won’t be angry with you, now tell me.”

“Kadyr-aga, we thought and thought, and we decided that you mustn’t be left all alone with little children. Only Allah knows if your wife will get well or not. So we looked for a bride for you and found a very good woman. She knows about you from hearsay and is willing to meet you. We want you to get to know her.”

Kadyr hadn’t been expecting a suggestion like that, and he got really angry:

“Don’t talk such nonsense! My wife is still alive. How could you say something like that? I won’t listen to you!”

But they carried on pressing their point:

“Kadyr-aga! We’ll all leave this world for the next, what’s to be done! And not many people manage to beat cancer. It’s such a terrible disease. Think about the children!”

Kadyr finally gave way to their persuasion and met the woman. They probably liked each other. They started something like an affair. He didn’t come to Ashkhabad, and he only phoned me occasionally. Kadyr’s sisters began gradually preparing for the wedding. They even named a possible day.

That was when Kadyr stopped phoning me completely.

Then after three months, with God’s help, I was still alive. And I came home.

When they discharged me from the hospital, the doctors had warned me that I mustn’t sleep with my husband. If I didn’t do as they said, I could die.

Kadyr and his sisters’ jaws dropped, they were so astonished, but they didn’t say anything to me. And so my husband’s wedding never happened!

But he put the question point-blank:

“Raya, please forgive me, of course, but I’m still young, I want to live a normal life, I want to sleep with you, but you can’t. What am I to do? Carry on living like this until I die?”

I answered my husband:

“Kadyr, I understand you, you’re still young. The only thing I ask of you, please Kadyr, for the sake of the children, don’t throw me out of the house!”

Kadyr agreed not to divorce me, but on one condition—that I wouldn’t try to stop him seeing other women on the side.

I agreed. I was an invalid, where could I go with three children? My parents were poor, and I was so weak, my mother used to come to help me. I didn’t go back to work for a long time.

Kadyr used to come home when he wanted. He had a car and a driver from his job. And he had a car of his own. But he was still a family man: he did repairs at home, he brought the groceries, he made sure we didn’t lack for anything. At night he kissed me and went to his own room, and I went to mine.

After a while we started getting strange phone calls. Different women used to call and abuse me:

“Hey you, leave Kadyr, I want to live with him!”

Or:

“You useless creature, I’m going to sleep with your husband!”

They tried to insult me and humiliate me any way they could, but I kept quiet and didn’t say anything to Kadyr about these calls. I swallowed everything.

Kadyr was a Party member, and by local standards we still didn’t have a very rich life. But he built houses for many of his mistresses, and many women exploited him (when he was the director of the brick factory). And he was very generous to his relatives too.

I can’t say he’s a bad man or a good one. If not for my illness, we’d have had a perfectly normal life.

What’s to be done, Bibish? It’s just my fate!

That was how she ended her story. I thought: How much women have to put up with!

And here’s something I can add to this story. When my father-in-law fell ill with cancer, Raya nursed him devotedly. Nobody else wanted him then. And so he died in her arms.

I am grateful to my mot

her-in-law, she taught me a lot: how to deal with people, always to be amicable, not to envy anyone, to treat my illnesses with folk medicine, to dress with taste—otherwise I used to go about dressed gaudily all the time, like a set of traffic lights—how to talk to everybody in the right way, how to receive guests . . . I thank God that I have such a good mother-in-law. I always call her Mom.

But let’s get back to my marriage. One day Ikram and I went to the bazaar together. They had a very big collective farm market, and a merchandise market beside it. Ikram wanted to show me all this. At the end, we went in to buy some fruit. There was everything, anything you could want, and all cheaper than in Russia. And I had a certain amount of my own money: my husband gave me it, and at the wedding people had thrown money onto my head too. So now I decided to spend some of it. Just then Ikram stopped to talk to someone and I went on among the fruit stalls. I walked along, looking for the cheapest apples and pomegranates, which meant they would be the worst too. I bought in a hurry, I don’t remember how much, probably about three kilograms. It was the first time I bought anything as a wife. And then Ikram came up to me and asked:

“Well, my dear, what have you bought? Let’s see what tasty things you have in your bag.” He opened the bag, looked in, and was upset straightaway: “Why did you buy such rotten ones? Give me the bag, so my parents won’t see, or else they say: ‘Have you been digging in the garbage heap?’” He took the bag from me and threw all the fruit onto the garbage heap. Then he came up to me and said: “There’s an old saying, ‘The miser pays twice over.’ So always buy only good fruit and good vegetables, that’s no way to live, eating things that are rotten and smell bad.”

I was very upset that he’d thrown out the fruit, because for as long as I could remember, in my childhood and my youth, I had eaten only cheap, half-rotten fruit like that. After all, my father hadn’t been able to feed us properly. There were nine children, how could all of us be fed with expensive fruit? And what about clothes? How much money was my father supposed to have? After all he was the only one in the family with a job.

Ikram bought new fruit—good fruit, large and not rotten—and I felt very awkward. And then we went back home from the collective farm market.

Dancer from Khiva, The

Dancer from Khiva, The