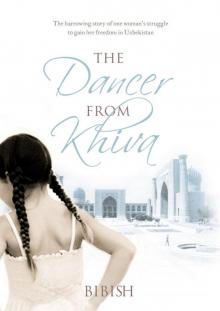

Dancer from Khiva, The Read online

Page 11

After that I got so used to eating pomegranates that Ikram used to buy them for me by the sackful.

One day the relatives asked my father-in-law:

“Well, how’s your daughter-in-law, is she getting used to city life? Are you pleased with her, or is she tricky and disobedient? Or perhaps bad-mannered? What’s your opinion of her?”

“She’s getting used to things, and we’re getting used to her. There are no complaints so far, everything’s all right. The only thing is, she eats an awful lot of pomegranates, we have to buy them by the sackful”—he laughed—“so if it goes on at this rate, our pay won’t be enough. Well, let her eat them and enjoy them, she’s welcome!”

And when he said that, everybody laughed.

We all got on very well together. They found me a job in an Uzbek school as a teacher in the elementary classes. My father-in-law was always saying:

“If only she could speak Russian, I could get her a job as a teaching methods specialist in the kindergarten. It’s a shame she can’t talk to anyone in Russian.”

At home they spoke to each other in Russian and only sometimes in Uzbek—that was when the father’s relatives came. And all the time I just listened to them and nodded my head.

One day we were sitting at the table—Ikram, his mother, and me—and just as I was saying something quickly, I don’t remember what, Ikram stopped me and said in Russian:

“Don’t rush!”

I stopped talking. I wanted to show that I’d understood. After a while I got up, went into the lounge, and found the Russian–Uzbek dictionary on the shelf. I wondered what “dontrush” meant. I looked right through the entire dictionary and couldn’t find the word “dontrush” anywhere. It turned out to be a phrase!

Another time my husband and I were lying in bed dreaming, and he said in Russian:

“One day the two of us will buy a hut!”

I didn’t know the word “hut,” so I went to look for it in the dictionary again, and didn’t find it anywhere. It turned out that “hut” was a Ukrainian word! I almost went crazy trying to find it! Only God knows how much I suffered to study the Russian language. And I promised myself: If I have children, to make life easier for them, I’ll put them in a special Russian school.

A year went by. I went to Tashkent twice for the exam sessions and visited my parents several times. My mother-in-law gave them a new television. Before that they only had an old Snezhok television. When my father brought it home in the late sixties, I remember our neighbors and friends came to have a look at it, because not all of them had televisions.

And so a year went by after the wedding. My mother-in-law was worried all the time that I hadn’t got pregnant, and my husband seemed to have lost hope that I would ever give him a child. Finally my mother-in-law took me to a gynecologist and I was treated for a long time. After the treatment I got pregnant. When they found out at home that I was finally pregnant, they wouldn’t let me work at all, in case I might have a miscarriage. They were concerned about me all the time, they said: “Don’t you get up, we’ll do it. And they said: “You mustn’t get excited, you mustn’t lift anything, rest!” While I was pregnant I swelled up for some reason, I don’t know why, maybe it was my kidneys, or because I used to sit in front of the television without moving.

One funny thing happened to me to do with that television. Basically, during the nine months when I was pregnant, I became like a real roly-poly. I was always sitting or lying on the divan and watching the television. One day the presenter on the Uzbek channel announced:

“Dear viewers! If you can see me, stop whatever you are doing and listen to this announcement. Here on the table there are flowers in a vase. Let me tell you that these flowers have been irradiated with Kashpirovsky’s rays. Come closer to the screen.”

I just barely managed to get up and move closer to the television.

The presenter said:

“Well now, viewers, I hope you have all moved closer to the screen, have you?”

I answered the announcer:

“Yes!”

The presenter went on:

“Even though these flowers are on the television, they are going to influence you. Sick people get well, and healthy people feel even better. So if you have moved closer to the screen, sniff the flowers.”

So I began sniffing the screen. The presenter said:

“Well now, can you smell that scent, it smells like spring, doesn’t it?”

I sniffed and sniffed at the television, then said to the screen:

“Yes, it does.”

The presenter said:

“If you have taken a good sniff and followed the whole procedure, well done. And now I’d like to wish you a happy April Fools’ Day, it was a joke, all the best, good-bye!”

I sat there on the floor completely confused. Just then my mother-in-law came into the room and asked:

“Why have you gone so close to the television? It’s bad for you!”

Then I told her what had happened. How she laughed! And she said:

“We keep telling you: don’t get up, don’t move, rest, and you’ve just been really heroic and walked as far as the television!”

Exactly nine months went by. I was worried all the time in case the child would be born on the thirteenth day of the month. Because I was born on January 13, on New Year’s Day in the old style, and I’d known nothing but suffering in life. It was already April 12, and I was walking around saying to myself: I mustn’t give birth on the thirteenth. Evening came, it was about eight o’clock, and I had one little pain in my stomach, then it instantly disappeared. But I decided: This is it, I’m having the child! I alarmed everyone in the house. My husband immediately took me and a female neighbor to the maternity home in his car. They brought me to the reception area and a nurse was there.

She asked:

“When did it start?”

I said:

“What?”

“The contractions—why, is this your first time, then?”

“Yes.”

“Right then, lie down and we’ll check.”

She checked me and said:

“My girl, your womb’s only just opened a little bit, a finger’s width. Why did you come so early?”

“I thought I was having the baby.”

She laughed, called my husband into the corridor, and told him:

“Her contractions are still weak, take her back home, or she’ll suffer here for a long time yet. Go, go home.”

I refused to go home.

“I won’t go.”

“Go home, my girl, or they might give you cesarean section.”

“I won’t go home,” I said, and began to cry.

“Why? It’s still too soon for you to give birth, he can bring you when you have serious contractions.”

“How will I be able to look my father-in-law in the eye, if I come back from the maternity home without having a child! What will he say?” How naive I was.

They barely managed to calm me down on the way back. When we got home, I felt so ashamed I went into my room as quickly as I could. My father-in-law rushed in from the lounge:

“What’s wrong, why did you come back?”

He really was surprised to see me. The neighbor explained to him that I would have to go to the maternity home again. The women began reassuring me. All night long I tormented myself, and then that thirteenth day of the month came.

When we were going to the maternity home, my husband said to me:

“Do you hear me, have a son, only a son! If it’s a girl, I won’t pick you up from the maternity home!”

There was another nurse on duty when we arrived. She took me to the ward. I asked her:

“Can I put off the birth until the fourteenth?”

She laughed:

“No, my dear, it’s time for you to give birth.”

In the ward I screamed for all I was worth. One woman came running up to me:

“Hold on, hold on, the fir

st time’s always like that—look, I’ve just had twins.” And she stroked my back.

The pain was terrible. I didn’t know what to do with myself, I went out into the corridor and shouted:

“Why did I ever sleep with you, I’ll never sleep with you again, never!” (That was about my husband.)

The doctors decided to give me a cesarean. My father-in-law didn’t agree, and he said:

“She’s young, let her give birth herself.”

His word was law.

The agonizing contractions lasted exactly twenty-two hours.

When the time came for me to give birth, they put me on the chair, and the doctor kept repeating:

“Come on, push, you’ll have the child now.”

I was so anxious I kept saying:

“What is it, a boy or a girl?”

The doctor said:

“To find out which it is, first you have to have the child! Come on now, push!”

For us in the East it’s very important for the first child to be a son, a man. I thought that if it was a girl, my husband really wouldn’t collect me from the maternity home. Afterward I realized it was a joke, and they only keep you in the maternity home for six or seven days.

And so I had my first son, Aibek, on April 13 after all.

A week later I came back from the maternity home, and my father-in-law congratulated me.

“This time you gave birth, then?” he laughed.

After my son was born I had to go to Tashkent almost straightaway for the final state exams.

My mother-in-law said:

“Ikram and his father can stay at home, and I’ll go with you. You can take the exams, and I’ll stay with my grandson, all right?”

We set off with the little baby, he was only twenty days old.

In Tashkent we stayed with a girl student in my year. I took the exams one after another. My mother-in-law and my child were always there, close to me.

By the way, my little son was a great help to me with the exams. Do you wonder how?

This is what I asked the other students in my year to do when they were standing in line for the exam in the corridor:

“I’ll go in, take a question ticket, and you immediately call out: ‘I beg your pardon! Siddikova’s baby is crying out here.’ So then I’ll come out, show you the ticket, and you write me a crib. Then I’ll go in, and as soon as you’ve written the answer, call me again, I’ll take the crib and go back in and answer the question.”

That was how I passed the first exam.

I breast-fed my child regularly, and everything was all right. At the last exam I was standing in the corridor with my child in my arms, and as always my mother-in-law was close by.

Then suddenly my stomach started hurting really badly. My mother-in-law got angry and said:

“Of course it will hurt, because you go around with nothing on. You ought to have dressed warmly, you’ve only just given birth. And you’re wearing nothing but your panties!”

My stomach hurt so badly that I couldn’t go into the auditorium. I went back with my mother-in-law and my baby to the apartment we’d rented for the exams. We put the baby on the bed. My pain kept on as bad as ever. My mother-in-law went into the kitchen, warmed up some cottonseed oil, then came up to me, lifted up my dress, and poured the hot oil onto my navel.

“Your bowels are probably inflamed.”

After that I simply couldn’t bear it, I almost fainted from the pain.

My mother-in-law took fright and dialed 03 for the ambulance. The ambulance came, but they couldn’t tell what was wrong, and they took me to a maternity home, because I’d recently given birth. At the maternity home, they kept me in reception for a long time and then said: “It’s not our kind of problem, you have to take her to the surgical department in the republican hospital.” Time passed while they were taking me there. But it turned out there wasn’t any time to lose. In the surgical department they said: “Acute phlegmonic appendicitis. Peritonitis.” It was almost too late to operate on me.

My baby and my mother-in-law had always been there beside me, everywhere I went. But now they took me into the operating theater, and my child was left without any breast milk. He was left out in the yard of the hospital with my mother-in-law.

Afterward my mother-in-law told me what happened to them.

She sat on a bench in the yard until eleven o’clock in the evening. They asked her: “What are you doing here so late?” She answered:

“I don’t know where I should go. They’ve just operated on my daughter-in-law, and her baby has no milk.”

My poor little boy was hungry, he kept looking for a nipple and crying all the time.

The doctors said:

“Where are you staying, tell us and we’ll take you home.”

But it was the first time my mother-in-law had been in Tashkent, she didn’t know how to explain, and so she answered:

“My daughter-in-law’s a student at the Institute of Culture, take me to the institute, then I’ll be able to get my bearings and find my house. If it’s not too much trouble, please take me to the institute.”

They took her where she asked. From there she found her bearings and walked to the place where we were staying, with the baby in her arms.

My son wouldn’t stop crying. Naturally, he was hungry and wet, because while they were waiting at the hospital they’d run out of diapers. My mother-in-law picked the baby up again and set off round the apartments. She knocked on doors and asked for something for the child: “Please give me some milk, even some dried milk for the little baby.” Some people didn’t even open their door, others said they didn’t have any milk. She was tired from walking, and the baby kept screaming all the time. My mother-in-law kept on and on walking and finally she found some dried milk, given to her by a woman, but even then it was out of date. She had to risk it, what else could she do? She came home, mixed the powder with water, and fed the child from a bottle. Early in the morning she got up, picked up the child again, and went to the grocery store. She brought back some milk in a jar and then fed the child with that.

After that she phoned Turkmenia and told them what had happened. Ikram immediately left for Tashkent. My mother-in-law sat in the apartment with the child, and my husband came to see me in the hospital every day and brought me food and fruit.

They wouldn’t let me feed my son or even see him, because when my appendix burst the pus and the infection had spread right through my body. I was in the hospital for exactly a month. And I was very worried that I hadn’t managed to take the final state exam. The doctors said that in a case like this the teacher or the exam commission from the institute ought to come to the hospital themselves. But alas, no one came. I started crying and asking the doctors to let me go, I thought I might still be able to take the exam with the other students. The doctors said:

“It’s too risky, the stitches could come open!”

I explained to them that I’d been studying for five years, and only the last exam was left and my five years would simply be wasted, and after the exam I’d get my diploma. “Please, let me go,” I begged them.

Then they took me to the institute in an ambulance. I climbed out of the ambulance with a stick, after that they wouldn’t allow me to walk any further, because the exam was on the third floor—I couldn’t have walked up there anyway. They asked the exam commission to look out the window to make sure I had really turned up. Of course they looked out the window and saw I could hardly walk. And they explained to them that my appendix had burst and I had a child only one month old, a suckling babe to look after. They looked at my earlier marks and decided to give me my final mark without taking the exam. And that was how I graduated from the institute.

After a month I was discharged, and I went back to Turkmenia with my husband, my child, and my mother-in-law. At home my father-in-law and his relatives were waiting for us. They celebrated my graduation from the institute and the fact that I was alive and well. They admired my s

on.

But a week later I fell ill again—this time one of my kidneys failed. They took me to the hospital in an ambulance again, and I had a high temperature for a week. And I couldn’t piss either, my bladder was inflamed.

I was in the urology ward for two and a half months. And again they wouldn’t let me see my son. When I was discharged from the hospital, he was three and a half months old. Because of all my illnesses I hadn’t been feeding him, and I was very worried.

When I came back home my mother-in-law immediately told me:

“He’s mine now. If you want a child, have another one.”

As soon as my mother-in-law told me to have a child, I got pregnant. Then my father-in-law suddenly fell ill, and the diagnosis was lung cancer. A few months later he died.

My mother-in-law sent me to the neighbors so that my son wouldn’t be frightened during the funeral. He was exactly one year old, and I was almost eight months pregnant.

When they didn’t see me at the funeral, my father-in-law’s relatives came looking for me at the neighbors’ house and began scolding me:

“Our brother slaved for you all, just for you, and you’re hiding. What will people say? That his daughter-in-law wasn’t at the service and she didn’t cry! Come on now, leave the child here, let’s go quickly, they’re about to take him to the cemetery! You have to cry with us.”

My mother-in-law didn’t say anything, she couldn’t contradict the relatives. I had to go with them. I walked into the room where the coffin was standing. Everyone there was weeping and keening and waving their arms around: “Why have you left us?,” “How are we going to live without you?,” “Oh, my sweet one!,” “Oh my darling!” That was the way they showed their grief. But there wasn’t a single tear in my eyes, even though I felt very sorry for him—he was only fifty-seven.

The relatives all looked at me reproachfully, and I had to think of something. I went through into the kitchen and took a knife and a couple of onions. There were a lot of people outside in the yard. I went into the bathroom without being noticed and started cleaning the onions with the knife. Then I rubbed them on my eyelids, my face, and my nose to make the tears appear. A few seconds later the tears started running from my eyes. Perfectly genuine tears! After that I simply couldn’t stop them.

Dancer from Khiva, The

Dancer from Khiva, The